|

0 Comments

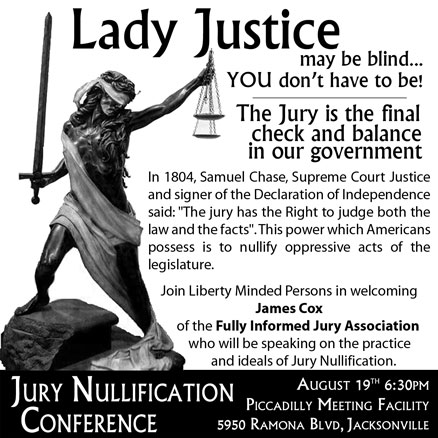

RSVP: here (...in our thoughts...worldwide!)

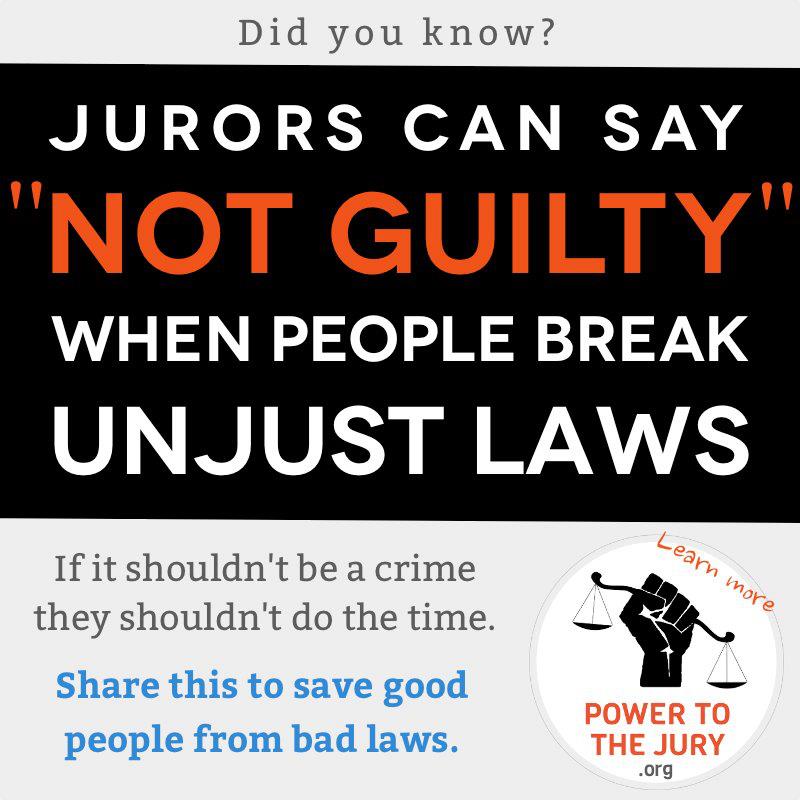

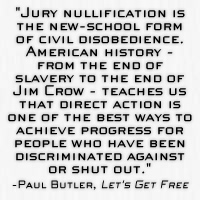

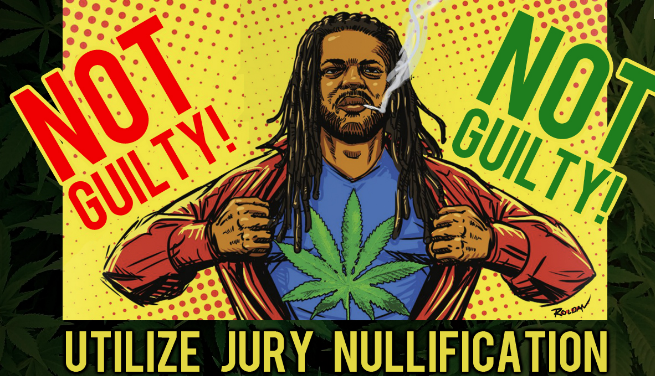

Jury nullification occurs when juries acquit criminal defendants who are technically guilty, but who do not deserve punishment. It occurs in a trial when a jury reaches a verdict contrary to the judge's instructions as to the law.

A jury verdict contrary to the letter of the law pertains only to the particular case before it. If a pattern of acquittals develops, however, in response to repeated attempts to prosecute a statutory offence, this can have the de facto effect of invalidating the statute. A pattern of jury nullification may indicate public opposition to an unwanted legislative enactment. In the past, it was feared that a single judge or panel of government officials may be unduly influenced to follow established legal practice, even when that practice had drifted from its origins. In most modern Western legal systems, however, juries are often instructed to serve only as "finders of facts", whose role it is to determine the veracity of the evidence presented, and the weight accorded to the evidence, to apply that evidence to the law and reach a verdict, but not to decide what the law is. Similarly, juries are routinely cautioned by courts and some attorneys to not allow sympathy for a party or other affected persons to compromise the fair and dispassionate evaluation of evidence during the guilt phase of a trial. These instructions are criticized by advocates of jury nullification. Some commonly cited historical examples of jury nullification involve the refusal of American colonial juries to convict a defendant under English law. Juries have also refused to convict due to the perceived injustice of a law in general, or the perceived injustice of the way the law is applied in particular cases. There have also been cases where the juries have refused to convict due to their own prejudices such as the race of one of the parties in the case. Other cases have revealed that some juries simply refuse to render a guilty verdict in the absence of overwhelming direct or scientific evidence to support such a judgment. With this type of jury impaneled for the trial of a case, even substantial and competently presented circumstantial evidence may be discounted or rendered inconsequential during the jury's deliberation. Read more. Jury nullification occurs when juries acquit criminal defendants who are technically guilty, but who do not deserve punishment. It occurs in a trial when a jury reaches a verdict contrary to the judge's instructions as to the law.

A jury verdict contrary to the letter of the law pertains only to the particular case before it. If a pattern of acquittals develops, however, in response to repeated attempts to prosecute a statutory offence, this can have the de facto effect of invalidating the statute. A pattern of jury nullification may indicate public opposition to an unwanted legislative enactment. In the past, it was feared that a single judge or panel of government officials may be unduly influenced to follow established legal practice, even when that practice had drifted from its origins. In most modern Western legal systems, however, juries are often instructed to serve only as "finders of facts", whose role it is to determine the veracity of the evidence presented, and the weight accorded to the evidence, to apply that evidence to the law and reach a verdict, but not to decide what the law is. Similarly, juries are routinely cautioned by courts and some attorneys to not allow sympathy for a party or other affected persons to compromise the fair and dispassionate evaluation of evidence during the guilt phase of a trial. These instructions are criticized by advocates of jury nullification. Some commonly cited historical examples of jury nullification involve the refusal of American colonial juries to convict a defendant under English law. Juries have also refused to convict due to the perceived injustice of a law in general, or the perceived injustice of the way the law is applied in particular cases. There have also been cases where the juries have refused to convict due to their own prejudices such as the race of one of the parties in the case. Other cases have revealed that some juries simply refuse to render a guilty verdict in the absence of overwhelming direct or scientific evidence to support such a judgment. With this type of jury impaneled for the trial of a case, even substantial and competently presented circumstantial evidence may be discounted or rendered inconsequential during the jury's deliberation. Read more. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2014

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed